Molybdenum

Molybdenum mine of JDC, close to Xi'an City in China

History

Molybdenum has a long and intriguing history, shaped by centuries of mistaken identity. In ancient times, molybdenum ores were often confused with lead ores and graphite, as their appearance and properties seemed similar. This confusion is reflected in the very name of the element: molybdenum derives from the ancient Greek word molybdos, meaning lead.

Although molybdenum minerals were known throughout history, the element itself was not recognized as distinct until the late 18th century. In 1778, the Swedish-German chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele successfully differentiated molybdenum from other metallic salts, marking its discovery as a new entity. Just a few years later, in 1781, the Swedish chemist Peter Jacob Hjelm achieved the first isolation of molybdenum metal. By reducing molybdenum oxide with carbon, he produced the metallic form, laying the foundation for future exploration of its properties and applications.

From confusion with lead to recognition as a unique element, molybdenum’s story reflects the evolution of chemistry itself—where careful observation and experimentation transformed ancient assumptions into modern scientific understanding

Properties

Molybdenum does not occur naturally as a free metal on Earth; instead, it is found in minerals in various oxidation states. When isolated, the element appears as a silvery metal with a subtle gray cast and is notable for having the sixth-highest melting point of any element. Its ability to form hard, stable carbides makes it invaluable in alloy production, and indeed, about 80% of global molybdenum output is consumed in the manufacture of steel alloys, including high-strength steels and superalloys.

Molybdenum is mined both as a principal ore and as a byproduct of copper and tungsten mining. China is the world’s largest producer, where the raw material undergoes several steps—roasting, concentration, and reduction—before becoming usable metal. Even in small proportions, molybdenum has a profound impact on steel performance. For example, 41xx steels typically contain between 0.25% and 8% molybdenum, and more than 43,000 tonnes of the element are incorporated annually into stainless steels, tool steels, cast irons, and high-temperature superalloys.

One of molybdenum’s most remarkable qualities is its ability to withstand extreme heat without significant expansion or softening. This property makes it indispensable in demanding environments such as military armor, aircraft components, electrical contacts, industrial motors, and filaments. Its resilience under intense thermal stress ensures that molybdenum remains a cornerstone material in both heavy industry and advanced engineering applications.

Molybdenum Products

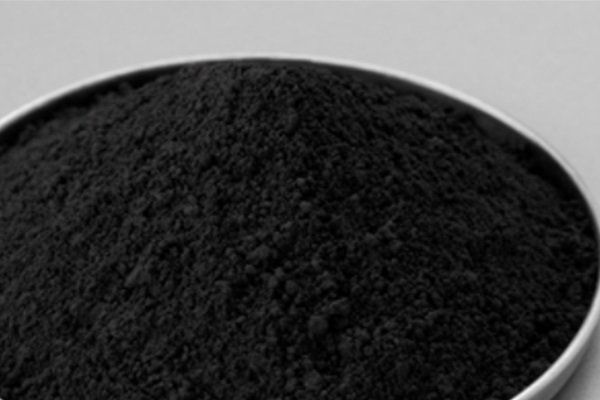

• Spherical or TZM Powder

• Molybdenum Powder or Blocks for stainless steel production (YMo55, YMo60)

• Concentrate Molydenum Powder (KMo-47, 49, 51, 53, 57)

• Molybdenum Iron, massive or granular (FeMo55, 60B, 60A, 65)

• Mo Plates, Rods, Targets, Boat, Tray, Disk, Plug, Strip

• Wire (also for cutting and for lighting)

• Components (Screws, Stands, Bolts, Stirrer)

• Electrodes (Glass melting)

• Mo Chemicals (Oxide, Sulfide, Disulfide, etc.)