Tantalum & Niobium

History

The story of tantalum begins in Sweden in 1802, when the chemist Anders Ekeberg first identified the element. Just a year earlier, Charles Hatchett had discovered columbium, now known as niobium. In 1809, the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston compared the oxide of columbite, with a density of 5.918 g/cm³, to that of tantalum, with a density of 7.935 g/cm³. Despite the difference in density, Wollaston concluded that the two oxides were identical and retained the name tantalum.

Following confirmation by Friedrich Wöhler, it was widely believed that columbium and tantalum were the same element. This assumption was challenged in 1846 by the German chemist Heinrich Rose, who argued that the mineral sample contained two distinct elements. He named them after the children of the mythological king Tantalus: niobium (from Niobe, the goddess of tears) and pelopium (from Pelops). Later research revealed that “pelopium” was not a new element but rather a mixture of tantalum and niobium, and that niobium was identical to Hatchett’s columbium discovered in 1801.

The differences between tantalum and niobium were finally demonstrated beyond doubt in 1864, settling the scientific debate. In 1903, Werner von Bolton produced the first relatively pure, ductile tantalum metal in Charlottenburg. Metallic tantalum wires were soon employed in light bulb filaments, though they were eventually replaced by tungsten due to its superior performance.

The name tantalum itself is rooted in Greek mythology, derived from Tantalus, the father of Niobe. Just as the myth evokes themes of thirst and denial, tantalum is famously resistant to absorbing acid, a property that inspired its enduring name.

Properties

Tantalum and niobium are essential metals in modern industry, valued for their ability to form alloys with high melting points, strength, and ductility. When combined with other metals, they are used to produce carbide tools for metalworking equipment and superalloys that serve in demanding environments such as jet engine components, chemical process equipment, nuclear reactors, and missile parts.

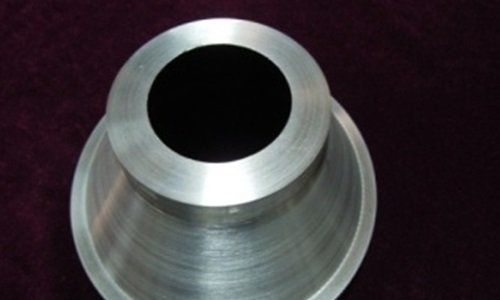

Tantalum is particularly prized for its chemical resistance. It remains inert against most acids, with the exception of hydrofluoric acid and hot sulfuric acid, and can also corrode in hot alkaline solutions. This resistance makes tantalum ideal for reaction vessels, pipes, and heat-exchanging coils used in corrosive chemical processes, such as the steam heating of hydrochloric acid. Historically, tantalum played a key role in the production of ultra-high frequency electron tubes for radio transmitters, where its ability to capture oxygen and nitrogen by forming nitrides and oxides helped maintain the high vacuum required for operation. Its high melting point and oxidation resistance also make tantalum suitable for vacuum furnace parts and a wide range of corrosion-resistant components, including thermowells, valve bodies, and specialized fasteners.

Niobium, meanwhile, has carved out a unique role in advanced technologies. It is a critical component of superconducting materials, often alloyed with titanium and tin, which are widely used in the superconducting magnets of MRI scanners. Beyond superconductivity, niobium finds applications in welding, nuclear industries, electronics, and optics. It is also valued in numismatics and jewelry, where its low toxicity and the striking iridescence produced by anodization make it both safe and visually appealing.

Together, tantalum and niobium embody the intersection of durability, resistance, and advanced functionality, enabling innovations across industries from heavy engineering to cutting-edge medical technology.

Our Products

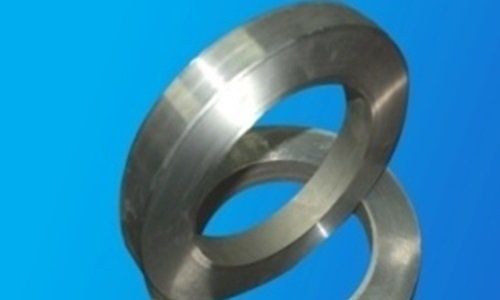

- Tantalum and Niobium in pure form as well as their alloys

- Melted or sintered quality

- all common delivery form