Tungsten (Wolfram)

Wolframite

History

The element known today as tungsten carries a name rooted in language and history. The word tungsten comes from the Swedish phrase tung sten, meaning “heavy stone,” and is used in English, French, and many other languages. Interestingly, the Nordic countries themselves do not use this name. In Sweden, tungsten originally referred to the mineral scheelite, while in most European languages—particularly Germanic and Slavic—the element is called wolfram, derived from the mineral wolframite. This dual heritage explains the chemical symbol W, which remains in use worldwide.

The scientific discovery of tungsten unfolded in the late 18th century. In 1781, the renowned chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele demonstrated that a new acid, tungstic acid, could be produced from scheelite. Together with Torbern Bergman, he suggested that reducing this acid might yield a new metal. Just two years later, in 1783, at the Royal Basque Society in Bergara, Spain, the brothers José and Fausto Elhuyar succeeded in isolating the metal by reducing tungstic acid with charcoal. Their achievement marked the true discovery of tungsten, establishing its place among the elements.

From its linguistic roots in “heavy stone” to its isolation in Spain, tungsten’s story reflects both cultural diversity and scientific ingenuity. Its dual names—tungsten and wolfram—remain a testament to the intertwined paths of language, mineralogy, and chemistry in the history of science.

Properties

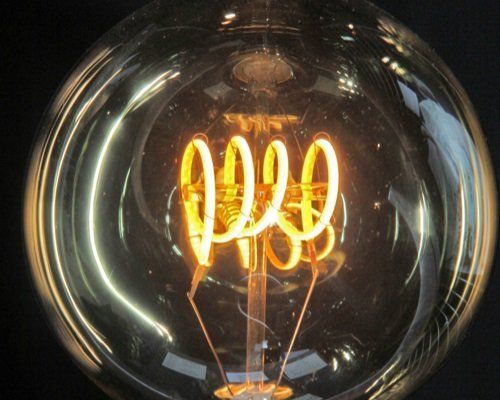

Tungsten’s unique combination of properties—resistance to high temperatures, exceptional hardness, and remarkable density—has made it one of the most important raw materials in modern industry, particularly in the arms sector where strength and durability are paramount. Its ability to retain strength at extreme temperatures, coupled with its high melting point, has led to widespread use in light bulb filaments, cathode-ray tubes, vacuum tubes, heating elements, and rocket engine nozzles. In aerospace and high-temperature engineering, tungsten is indispensable for electrical, heating, and welding applications, most notably in gas tungsten arc welding (TIG welding), where its stability ensures reliable performance.

Beyond its mechanical resilience, tungsten’s conductive properties and chemical inertness make it valuable in precision technologies. It is used in electrodes and in the emitter tips of electron-beam instruments, such as electron microscopes, where field emission guns demand materials of exceptional stability. In electronics, tungsten serves as an interconnect material in integrated circuits, bridging silicon dioxide dielectric layers and transistors. It also appears in metallic films, replacing conventional wiring with thin coats of tungsten or molybdenum on silicon substrates.

Tungsten’s electronic structure further enhances its versatility. It is a primary material for X-ray targets and is widely employed in shielding against high-energy radiation, including in the radiopharmaceutical industry for protecting radioactive samples like FDG. In gamma imaging, tungsten’s shielding properties make it ideal for coded apertures. Tungsten powder also finds use as a filler in plastic composites, providing a nontoxic substitute for lead in bullets, shot, and radiation shields. Its thermal expansion closely matches that of borosilicate glass, enabling reliable glass-to-metal seals in specialized applications.

Finally, tungsten’s performance can be enhanced through potassium doping, which increases shape stability. This innovation prevents filaments from sagging or deforming under prolonged use, ensuring consistent functionality in high-temperature environments. Together, these qualities make tungsten a cornerstone of industries ranging from defense and aerospace to electronics, medicine, and advanced manufacturing.

Our products

- Tungsten in pure form as well as alloys

- all common delivery form

China is by far the biggest tungsten producer in the world! (>80% of the global concentrate production)